|

|

Railroad Paper

In the course of their operations, railroads issued an enormous amount

of paper items of various kinds, and just about all of these are of interest

to collectors. Of course like any other collectible, scarcity is a main

determinant of value, so some items that were produced in small quantities

-- like passes -- have more value than common items such as bills of

lading. Also, paper items from obscure but popular railroads such as

the Colorado narrow gauge lines command more attention than similar items

from the larger, more well-known companies. Lately it seems that paper

collectibles have come into their own with impressive auction prices

being realized for older public timetables and passes. However, all things

considered, paper still represents a good entry point to railroadiana-collecting

since many items are still obtainable for reasonable prices.

Railroad paper was produced for four basic audiences: investors, the

public, shippers, and employees. Investors were the first audience for

the obvious reason that money had to be raised for construction. However,

this rapidly changed to the traveling public and shippers in order to

raise revenues. When the majority of ordinary people traveled by rail,

a great deal of advertising was aimed at enticing travelers to choose

a particular railroad, route, or vacation destination. In the first decades

of the twentieth century, travel promotion reached a high art form with

specially commissioned illustrations and artwork. Today much of this

art, in the form of posters, public timetable covers, luggage stickers,

and other items, are especially prized by collectors. At one time, the

prevalent philosophy among railroad management was that an attractive

passenger service led to increased business in freight traffic, so passenger

business promotion was also considered an aid to the freight business.

However, there were special paper items aimed at shippers and companies,

most notably maps that illustrated the obvious convenience of a particular

route. In terms of quantity, probably the most paper generated by railroads

was for the benefit of internal operations, for example, employee timetables,

train orders, rule books, and other operational documents. Railroad paper was produced for four basic audiences: investors, the

public, shippers, and employees. Investors were the first audience for

the obvious reason that money had to be raised for construction. However,

this rapidly changed to the traveling public and shippers in order to

raise revenues. When the majority of ordinary people traveled by rail,

a great deal of advertising was aimed at enticing travelers to choose

a particular railroad, route, or vacation destination. In the first decades

of the twentieth century, travel promotion reached a high art form with

specially commissioned illustrations and artwork. Today much of this

art, in the form of posters, public timetable covers, luggage stickers,

and other items, are especially prized by collectors. At one time, the

prevalent philosophy among railroad management was that an attractive

passenger service led to increased business in freight traffic, so passenger

business promotion was also considered an aid to the freight business.

However, there were special paper items aimed at shippers and companies,

most notably maps that illustrated the obvious convenience of a particular

route. In terms of quantity, probably the most paper generated by railroads

was for the benefit of internal operations, for example, employee timetables,

train orders, rule books, and other operational documents.

The variety of railroad paper is almost unlimited, but there are a number

of popular categories that receive most of the collector interest in

this area. Without any claims to be comprehensive, here is a brief overview

of some of them:

Annual

Reports. These documents were produced primarily for stockholders

and investors and, therefore, are sometimes overlooked as the specialty

of economic historians. However, a wealth of information regarding

operations and equipment can be obtained from such reports in addition

to financial matters. Generally, annual reports were no-nonsense documents

meant to convey financial solidity and propriety rather excitement.

Usually they have plain covers, although starting around the 1950's,

railroads started issuing annual reports with flashier cover designs

and pictures in the interior. Many early annual reports contained attractive

maps that were elaborate documents in their own right. In fact, many

railroad maps that show up in today's market were originally published

in the back of annual reports. Right: An 1893 Annual

Report from the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway, with a typical

plain cover. Annual

Reports. These documents were produced primarily for stockholders

and investors and, therefore, are sometimes overlooked as the specialty

of economic historians. However, a wealth of information regarding

operations and equipment can be obtained from such reports in addition

to financial matters. Generally, annual reports were no-nonsense documents

meant to convey financial solidity and propriety rather excitement.

Usually they have plain covers, although starting around the 1950's,

railroads started issuing annual reports with flashier cover designs

and pictures in the interior. Many early annual reports contained attractive

maps that were elaborate documents in their own right. In fact, many

railroad maps that show up in today's market were originally published

in the back of annual reports. Right: An 1893 Annual

Report from the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway, with a typical

plain cover.

Blotters. Before

the advent of ball-point pens and when fountain pens were the dominant

writing instrument, an inexpensive and effective promotional item was

the blotter. Typically about 4 by 8 inches in size, blotters were used

to promote freight or passenger service and frequently provided information

on specific trains or routes. They could be quite colorful and often

featured special artwork. Right: A blotter advertising the "Night

Hawk", an overnight train between St. Louis and Kansas City operated

by the Burlington (Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad and the

Alton Railroad, date unknown. Blotters. Before

the advent of ball-point pens and when fountain pens were the dominant

writing instrument, an inexpensive and effective promotional item was

the blotter. Typically about 4 by 8 inches in size, blotters were used

to promote freight or passenger service and frequently provided information

on specific trains or routes. They could be quite colorful and often

featured special artwork. Right: A blotter advertising the "Night

Hawk", an overnight train between St. Louis and Kansas City operated

by the Burlington (Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad and the

Alton Railroad, date unknown.

Calendars. At

one time, it was common practice for railroads to issue an annual calendar

as a promotional item. In the first half of the 20th Century, calendars

were usually illustrated with specially commissioned art, some of it

achieving great acclaim and artistic recognition. Probably the two most

famous series in this regard were Winold Reiss' magnificent portraits

of Blackfeet Indians which graced the calendars of the Great Northern

Railway over roughly two decades, and the paintings of Grif Teller which

depicted dramatic industrial scenes along the Pennsylvania Railroad.

By the early 1960's as passenger traffic dwindled to the point of no

return, most railroads dropped the annual calendar as a promotional device,

although a few railroads, notably Norfolk Southern and Union Pacific

have continued the practice to the present day. Today those early 20th

Century calendars that have survived are eagerly sought by collectors,

with special emphasis placed on completeness (full calendar pads) and,

of course, good condition. Right: A 1938 wall calendar from the Chicago,

Burlington & Quincy Railroad, A.K.A. the "Burlington". Calendars. At

one time, it was common practice for railroads to issue an annual calendar

as a promotional item. In the first half of the 20th Century, calendars

were usually illustrated with specially commissioned art, some of it

achieving great acclaim and artistic recognition. Probably the two most

famous series in this regard were Winold Reiss' magnificent portraits

of Blackfeet Indians which graced the calendars of the Great Northern

Railway over roughly two decades, and the paintings of Grif Teller which

depicted dramatic industrial scenes along the Pennsylvania Railroad.

By the early 1960's as passenger traffic dwindled to the point of no

return, most railroads dropped the annual calendar as a promotional device,

although a few railroads, notably Norfolk Southern and Union Pacific

have continued the practice to the present day. Today those early 20th

Century calendars that have survived are eagerly sought by collectors,

with special emphasis placed on completeness (full calendar pads) and,

of course, good condition. Right: A 1938 wall calendar from the Chicago,

Burlington & Quincy Railroad, A.K.A. the "Burlington".

Employee

Timetables. Railroads have always issued timetables for the exclusive

use of their employees, a practice that continues to this day. Typically

such timetables provide information on physical plant, tonnage ratings

of locomotives, special conditions along the line, schedules of regular

trains, and other information of vital interest to railroad operation.

Probably no other single document gives such a telling picture of a

railroad's operation in a particular time period. In appearance, employee

timetables tend to be plain, no-nonsense booklets. Early examples were

often large in size (roughly 8 inches by 14 inches), and these are

sometimes referred to as "horseblanket" style. Gradually

railroads switched to the standard "timetable size" variety

(4" by 8"), although this transition did not occur all at

once. According to Tom Greco, Eastern roads were the first to do so,

with Midwestern and Western roads generally making the switch in the

1930's and 1940's. However, one railroad, the Canadian Pacific Railway,

used the large size until 1967. In recent years, many employee timetables

have been issued in binders. Right: A "horseblanket style" employee

timetable from the Oregon, Washington Railroad & Navigation Company,

a subsidiary of the Union Pacific system from November 14, 1920. Employee

Timetables. Railroads have always issued timetables for the exclusive

use of their employees, a practice that continues to this day. Typically

such timetables provide information on physical plant, tonnage ratings

of locomotives, special conditions along the line, schedules of regular

trains, and other information of vital interest to railroad operation.

Probably no other single document gives such a telling picture of a

railroad's operation in a particular time period. In appearance, employee

timetables tend to be plain, no-nonsense booklets. Early examples were

often large in size (roughly 8 inches by 14 inches), and these are

sometimes referred to as "horseblanket" style. Gradually

railroads switched to the standard "timetable size" variety

(4" by 8"), although this transition did not occur all at

once. According to Tom Greco, Eastern roads were the first to do so,

with Midwestern and Western roads generally making the switch in the

1930's and 1940's. However, one railroad, the Canadian Pacific Railway,

used the large size until 1967. In recent years, many employee timetables

have been issued in binders. Right: A "horseblanket style" employee

timetable from the Oregon, Washington Railroad & Navigation Company,

a subsidiary of the Union Pacific system from November 14, 1920.

Luggage

Stickers. A seemingly lost practice among transportation providers

is the issuance of colorful luggage stickers to place on suitcases

and trunks. Railroads did this at one time, and many of these were

vivid and colorful. Right: A luggage sticker from the Chicago, Milwaukee,

St. Paul & Pacific Railway advertising its premier "Olympian" passenger

train to the Pacific Northwest. Luggage

Stickers. A seemingly lost practice among transportation providers

is the issuance of colorful luggage stickers to place on suitcases

and trunks. Railroads did this at one time, and many of these were

vivid and colorful. Right: A luggage sticker from the Chicago, Milwaukee,

St. Paul & Pacific Railway advertising its premier "Olympian" passenger

train to the Pacific Northwest.

Maps. Since railroad construction literally put many towns and

place names on the map, it is natural that railroads would take a leading

role in issuing maps of their territory. As mentioned above, many early

maps were produced in association with materials aimed at investors;

however, gradually they were seen as a means of  promoting

both passenger and freight business. There were essentially two variations

here: the folding map and the wall map. The former could be quite large

when unfolded but was printed on fairly light-weight paper and folded

into a timetable size document for storage. In contrast the wall map

was printed on heavier weight material and designed to be displayed rather

than folded. Old photos of railroad business offices frequently show

a wall map prominently displayed, and not uncommonly, the map is from

another railroad! Regardless of whether it was a folding map or wall

map, the railroad's lines would be shown in the context of the entire

country or, less commonly, only in the portion of the country where the

railroad operated. The railroad's own lines were always highlighted prominently,

while competitors' lines were faint by comparison. Also the lines would

often appear to be more direct (straighter) than they actually were,

obliterating, for example, a jog that the line actually took to avoid

a mountain range. This was, of course, intended to convince a shipper

that the route was in fact a "straight shot" and therefore

the best choice for a shipment. Map collecting is a hobby in its own

right, and since many early domestic maps were railroad-originated, there

is little wonder that fine, early railroad maps command serious interest

($$). Right: A desk map folded "timetable size" and issued

by the Southern Pacific Railroad in the late 1920's. The "Four Great

Routes" refer to the "Sunset Route" between New Orleans

and San Francisco, the "Overland Route" between Chicago and

San Francisco, the "Shasta Route" between San Francisco and

Portland, and the "Golden State Route" between Chicago and

Southern California. promoting

both passenger and freight business. There were essentially two variations

here: the folding map and the wall map. The former could be quite large

when unfolded but was printed on fairly light-weight paper and folded

into a timetable size document for storage. In contrast the wall map

was printed on heavier weight material and designed to be displayed rather

than folded. Old photos of railroad business offices frequently show

a wall map prominently displayed, and not uncommonly, the map is from

another railroad! Regardless of whether it was a folding map or wall

map, the railroad's lines would be shown in the context of the entire

country or, less commonly, only in the portion of the country where the

railroad operated. The railroad's own lines were always highlighted prominently,

while competitors' lines were faint by comparison. Also the lines would

often appear to be more direct (straighter) than they actually were,

obliterating, for example, a jog that the line actually took to avoid

a mountain range. This was, of course, intended to convince a shipper

that the route was in fact a "straight shot" and therefore

the best choice for a shipment. Map collecting is a hobby in its own

right, and since many early domestic maps were railroad-originated, there

is little wonder that fine, early railroad maps command serious interest

($$). Right: A desk map folded "timetable size" and issued

by the Southern Pacific Railroad in the late 1920's. The "Four Great

Routes" refer to the "Sunset Route" between New Orleans

and San Francisco, the "Overland Route" between Chicago and

San Francisco, the "Shasta Route" between San Francisco and

Portland, and the "Golden State Route" between Chicago and

Southern California.

Menus. To

compete for business in the heyday of passenger train travel, railroads

operated first class food service in their dining cars. These were literally

restaurants on wheels, complete with special china, silverware, linens,

and, of course, menus. To examine such menus from our vantage point in

time is to be impressed by the type of food that could be freshly prepared

in a rocking dining car kitchen little bigger than a closet. Also impressive

are the low prices, although these naturally have to be judged in light

of the pay scales of the day. Many railroad menus were produced with

beautiful covers, sometimes customized for special charter groups. Early

examples often featured illustrations and artwork on their covers, while

later examples (from the1950's on) tended to use photographs. Right:

A menu from the Canadian Pacific Railway dating from the late 1920's

and featuring a beautiful cover on the Maple Sugar Industry. This menu

lists a broiled half chicken for $1.25 and a sirloin steak for $1.50. Menus. To

compete for business in the heyday of passenger train travel, railroads

operated first class food service in their dining cars. These were literally

restaurants on wheels, complete with special china, silverware, linens,

and, of course, menus. To examine such menus from our vantage point in

time is to be impressed by the type of food that could be freshly prepared

in a rocking dining car kitchen little bigger than a closet. Also impressive

are the low prices, although these naturally have to be judged in light

of the pay scales of the day. Many railroad menus were produced with

beautiful covers, sometimes customized for special charter groups. Early

examples often featured illustrations and artwork on their covers, while

later examples (from the1950's on) tended to use photographs. Right:

A menu from the Canadian Pacific Railway dating from the late 1920's

and featuring a beautiful cover on the Maple Sugar Industry. This menu

lists a broiled half chicken for $1.25 and a sirloin steak for $1.50.

Name

Train Brochures. When railroads instituted a new train, particularly

one with a special name, they often produced brochures to announce

the event. This was especially true during the "last hurrah" of

private passenger train innovation -- in the late 1940's and early

1950's when many railroads rolled out postwar streamliners in an effort

to revive the passenger train business. From observation, the name

train brochures produced during this period show some of the finest

commercial illustration and design quality of any category of railroad

paper. Because of their relatively new vintage, these brochures have

tended to be rather inexpensive until recently when collectors have

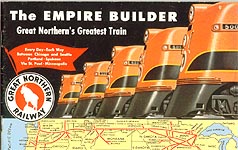

begun to recognize their esthetic value. Right: A name train brochure

from the Great Northern Railway introducing its new, streamlined "Empire

Builder" in 1949. Name

Train Brochures. When railroads instituted a new train, particularly

one with a special name, they often produced brochures to announce

the event. This was especially true during the "last hurrah" of

private passenger train innovation -- in the late 1940's and early

1950's when many railroads rolled out postwar streamliners in an effort

to revive the passenger train business. From observation, the name

train brochures produced during this period show some of the finest

commercial illustration and design quality of any category of railroad

paper. Because of their relatively new vintage, these brochures have

tended to be rather inexpensive until recently when collectors have

begun to recognize their esthetic value. Right: A name train brochure

from the Great Northern Railway introducing its new, streamlined "Empire

Builder" in 1949.

Passes. From

the very beginning of the industry, railroads occasionally needed to

provide free transportation to individuals. For example, officials of

other roads were sometimes given a tour of the lines, prospective shippers

were invited to examine facilities before agreeing to contracts; employees

needed to be transported to a work site, and so forth. The mechanism

for regulating such free transportation was the pass. Typically a pass

took the form of a small piece of cardstock, about the size of a modern

credit card with dimensions that allowed them to fit in a wallet. Passes

can be found from extremely early and obscure railroads, including those

that had little or no passenger service. In this respect, passes represent

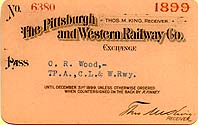

one of the few tangible remnants from many long-gone lines. Right: An

1899 pass from the Pittsburgh & Western Railway. Passes. From

the very beginning of the industry, railroads occasionally needed to

provide free transportation to individuals. For example, officials of

other roads were sometimes given a tour of the lines, prospective shippers

were invited to examine facilities before agreeing to contracts; employees

needed to be transported to a work site, and so forth. The mechanism

for regulating such free transportation was the pass. Typically a pass

took the form of a small piece of cardstock, about the size of a modern

credit card with dimensions that allowed them to fit in a wallet. Passes

can be found from extremely early and obscure railroads, including those

that had little or no passenger service. In this respect, passes represent

one of the few tangible remnants from many long-gone lines. Right: An

1899 pass from the Pittsburgh & Western Railway.

Public

Timetables. Passenger train or "public" timetables can

be found in a variety of forms, from plain, single-sheet schedules

describing service by a single railroad to large, poster-size schedules

(called "broadsides") that typically describe all the arrivals

and departures of one station. Most common are "timetable size" (4" by

8") booklets issued by a single railroad covering all passenger

trains operated by that company for a given time period. Like employee

timetables, passenger timetables offer a fascinating insight into railroad

operations during a given historical period. All timetables provided

arrival and departure times for specific trains, but many also provided

information on equipment assignments (number of coaches, sleeping cars,

etc.), fares, travel advice, and route descriptions. Some were rather

plain and utilitarian in design while others were quite colorful with

ornate cover art. The collection and study of passenger timetables

constitutes a specialty within the hobby, and there is even an organization

devoted exclusively to this activity. Right: An January, 1904 public

timetable from the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company. By this

time in history, the O.R. & N. Co. had become affiliated with the

Union Pacific System, hence the latter's "Overland Shield" logo

on the cover. Public

Timetables. Passenger train or "public" timetables can

be found in a variety of forms, from plain, single-sheet schedules

describing service by a single railroad to large, poster-size schedules

(called "broadsides") that typically describe all the arrivals

and departures of one station. Most common are "timetable size" (4" by

8") booklets issued by a single railroad covering all passenger

trains operated by that company for a given time period. Like employee

timetables, passenger timetables offer a fascinating insight into railroad

operations during a given historical period. All timetables provided

arrival and departure times for specific trains, but many also provided

information on equipment assignments (number of coaches, sleeping cars,

etc.), fares, travel advice, and route descriptions. Some were rather

plain and utilitarian in design while others were quite colorful with

ornate cover art. The collection and study of passenger timetables

constitutes a specialty within the hobby, and there is even an organization

devoted exclusively to this activity. Right: An January, 1904 public

timetable from the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company. By this

time in history, the O.R. & N. Co. had become affiliated with the

Union Pacific System, hence the latter's "Overland Shield" logo

on the cover.

Postcards. In

the early part of the twentieth century, when railroads were at their

zenith as passenger transportation, a immense number of postcards were

produced of railroad scenes. Typically these were used as a means of

communication when traveling or sightseeing. Specific subjects included

railroad stations, scenic rights-of-way, rolling stock, railroad engineering

landmarks, and even wrecks. Railroad postcards are fascinating today

because they provide a glimpse of a different era of travel, and many

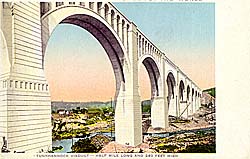

show scenes that are long vanished. Right: A postcard

of Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad's Tunkhannock Viaduct

shortly after it was built around 1915. This landmark still exists and

is in use. Postcards. In

the early part of the twentieth century, when railroads were at their

zenith as passenger transportation, a immense number of postcards were

produced of railroad scenes. Typically these were used as a means of

communication when traveling or sightseeing. Specific subjects included

railroad stations, scenic rights-of-way, rolling stock, railroad engineering

landmarks, and even wrecks. Railroad postcards are fascinating today

because they provide a glimpse of a different era of travel, and many

show scenes that are long vanished. Right: A postcard

of Delaware, Lackawanna & Western Railroad's Tunkhannock Viaduct

shortly after it was built around 1915. This landmark still exists and

is in use.

Route

Guides. Railroads met their passengers' interest in the route they

were traveling with guides that described points of interest along

the way. In some instances, there were separate versions of these guides

for each direction (East and West or North and South). For the most

part, such guides were produced only by those lines that traveled appreciable

distances through areas known for scenic beauty, both in the East and

West. They are particularly interesting nowadays in describing cities

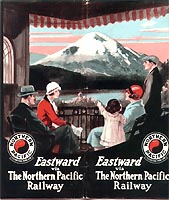

and localities as they existed a half century or more ago. Right:

An "Eastward" route guide produced by the Northern Pacific

Railway. It dates from the 1920's. Route

Guides. Railroads met their passengers' interest in the route they

were traveling with guides that described points of interest along

the way. In some instances, there were separate versions of these guides

for each direction (East and West or North and South). For the most

part, such guides were produced only by those lines that traveled appreciable

distances through areas known for scenic beauty, both in the East and

West. They are particularly interesting nowadays in describing cities

and localities as they existed a half century or more ago. Right:

An "Eastward" route guide produced by the Northern Pacific

Railway. It dates from the 1920's.

Rulebooks. Railroads

typically published a wide range of little booklets for employees covering

rules, regulations, tariffs, union agreements, and other necessary operational

information. These are almost always pocket-sized, about 3" by 5" and

usually have plain, brown covers. Illustrations in these booklets are

minimal, usually consisting of signal indications and other simply drawn

diagrams. In the case of rule books, however, their plainness was no

indication of importance. Since all operating employees had to pass rules

exams, these books were intensely scrutinized, and it is not uncommon

to find surviving books that are especially worn and full of notations. Right:

A rule book from the Western Maryland Railway dated 1915 and entitled "Rules

and Instructions Governing Free Travel and Passes." The contents

of this book are presented separately on this website. Rulebooks. Railroads

typically published a wide range of little booklets for employees covering

rules, regulations, tariffs, union agreements, and other necessary operational

information. These are almost always pocket-sized, about 3" by 5" and

usually have plain, brown covers. Illustrations in these booklets are

minimal, usually consisting of signal indications and other simply drawn

diagrams. In the case of rule books, however, their plainness was no

indication of importance. Since all operating employees had to pass rules

exams, these books were intensely scrutinized, and it is not uncommon

to find surviving books that are especially worn and full of notations. Right:

A rule book from the Western Maryland Railway dated 1915 and entitled "Rules

and Instructions Governing Free Travel and Passes." The contents

of this book are presented separately on this website.

Settlement

Publications. Publications that were designed to entice settlement

rather than just travel were common in the early days of railroad construction,

most particularly in the West. The Western U.S. and Canadian transcontinental

lines were built through remote territory that had little on-line business

or population, so one of the main efforts of early railroad builders

was to promote settlement along their lines. Accordingly, they produced

booklets of statistics and information related to farming, ranching,

and other livelihoods to be distributed both domestically and abroad

to prospective settlers. Of course, the general tone of these publications

was one of future success and prosperity, and undoubtedly more than

one settler discovered that the picture presented was a little too

rosy! Right: A 1914 settlement booklet from the Great Northern

Railway describing the benefits of taking up residence in the state

of Washington and province of British Columbia. The booklet was part

of a series of booklets providing "accurate information for the

land-hungry." Settlement

Publications. Publications that were designed to entice settlement

rather than just travel were common in the early days of railroad construction,

most particularly in the West. The Western U.S. and Canadian transcontinental

lines were built through remote territory that had little on-line business

or population, so one of the main efforts of early railroad builders

was to promote settlement along their lines. Accordingly, they produced

booklets of statistics and information related to farming, ranching,

and other livelihoods to be distributed both domestically and abroad

to prospective settlers. Of course, the general tone of these publications

was one of future success and prosperity, and undoubtedly more than

one settler discovered that the picture presented was a little too

rosy! Right: A 1914 settlement booklet from the Great Northern

Railway describing the benefits of taking up residence in the state

of Washington and province of British Columbia. The booklet was part

of a series of booklets providing "accurate information for the

land-hungry."

Tickets

and Ticket Folders. Tickets for passenger train travel were issued

in the millions but good examples are not necessarily that common.

After all, they were of temporary value and most were collected and

destroyed. How many of us save the remnants of our airline tickets?

In addition to the tickets themselves, the ticket envelopes that accompanied

them are also very collectible, especially those that are colorful

or illustrated. Right: A ticket issued by the Baltimore & Ohio

Railroad for a trip from Washington, PA. to Wheeling, WV on a special

college excursion train, Saturday, June 17th, 1911. Tickets

and Ticket Folders. Tickets for passenger train travel were issued

in the millions but good examples are not necessarily that common.

After all, they were of temporary value and most were collected and

destroyed. How many of us save the remnants of our airline tickets?

In addition to the tickets themselves, the ticket envelopes that accompanied

them are also very collectible, especially those that are colorful

or illustrated. Right: A ticket issued by the Baltimore & Ohio

Railroad for a trip from Washington, PA. to Wheeling, WV on a special

college excursion train, Saturday, June 17th, 1911.

Travel

Brochures. To promote vacation travel, railroads issued attractive

booklets describing the qualities of destination points served by their

lines. In fact, specific railroads became strongly associated in the

public mind with particular geographic localities, for example, the

Great Northern Railway with Glacier Park, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa

Fe Railway with the Grand Canyon, and the New York Central Railroad

with the Adirondack Mountains and Hudson River Valley. Because these

brochures were usually aimed at the leisure traveler, attractiveness

was critical. Covers were often illustrated with special artwork, and

interiors usually contained enticing drawings or photographs as well

as richly evocative descriptions. Today these brochures describe a

view of travel that is notably different from the contemporary emphasis

on thrills and theme destinations. While not ignoring exciting activities,

they seem to put more emphasis on serenity, relaxation, the subtleties

of nature, and a strong sense of place. Nostalgia for a different,

seemingly lost approach to travel is a major side effects of reading

these brochures. Right: A brochure by the New York Central

Railroad describing the beauties of the Adirondack Mountains, Thousand

Islands area, and Saratoga Springs. It dates from the late 1920's. Travel

Brochures. To promote vacation travel, railroads issued attractive

booklets describing the qualities of destination points served by their

lines. In fact, specific railroads became strongly associated in the

public mind with particular geographic localities, for example, the

Great Northern Railway with Glacier Park, the Atchison, Topeka & Santa

Fe Railway with the Grand Canyon, and the New York Central Railroad

with the Adirondack Mountains and Hudson River Valley. Because these

brochures were usually aimed at the leisure traveler, attractiveness

was critical. Covers were often illustrated with special artwork, and

interiors usually contained enticing drawings or photographs as well

as richly evocative descriptions. Today these brochures describe a

view of travel that is notably different from the contemporary emphasis

on thrills and theme destinations. While not ignoring exciting activities,

they seem to put more emphasis on serenity, relaxation, the subtleties

of nature, and a strong sense of place. Nostalgia for a different,

seemingly lost approach to travel is a major side effects of reading

these brochures. Right: A brochure by the New York Central

Railroad describing the beauties of the Adirondack Mountains, Thousand

Islands area, and Saratoga Springs. It dates from the late 1920's.

Summary. The categories of railroad paper discussed here are

by no means exhaustive. Some additional categories of railroad-originated

paper are employee magazines, recipe booklets issued by railroad dining

care departments, stock certificates, and informational booklets describing

facilities such as yards. To these can be added the enormous variety

of forms - train orders, bills of lading, dispatcher sheets etc., --

that were used in day-to-day operations as well as business documents

such as correspondence and letters. But wait...there's more. Documents

issued by some railroad suppliers and manufacturers, for example catalogs

from Baldwin Locomotive Works or Adams & Westlake, makers of lanterns

and railroad hardware, are generally considered railroad paper. So the

list is almost endless.

The good news is that much railroad paper is still relatively inexpensive

compared to hardware such as lanterns. In addition, there is much history

in this paper -- not necessarily the grand history of corporations but

rather the history of day-to-day life as it was experienced by travelers,

employees, and anyone else who had some contact with the railroads. Probably

no other category of railroad collectible offers such a rich potential

for new information.

Notes

Further Reading: Only one book has been published

on the general topic of railroad paper, although other books have discussed

it in the context of general railroadiana. That one book is by Brad Lomazzi's Railroad

Timetables, Travel Brochures & Posters, published in 1995

by Golden Hill Press, Spencertown, NY 12165. In addition, Carlos

Schwantes' Railroad Signatures Across the Pacific Northwest, published

by the University of Washington Press in 1991, has an extensive discussion

of the use of printed materials by railroads in this region as well as

some beautifully reproduced examples. |