|

|

"With

Tongues of Fire: Railroad Lanterns

by Bill Knapke

[This

article by Bill Knapke first appeared in the January, 1953 issue of Railroad

magazine. It is one of the very few reports on railroad lanterns by someone

who actually used them on the railroad, beginning in the late 1880's.

Bill uses a lot of railroad slang, so for those who might be unfamiliar

with some terms, a brief glossary is presented

at the end of the article.] [This

article by Bill Knapke first appeared in the January, 1953 issue of Railroad

magazine. It is one of the very few reports on railroad lanterns by someone

who actually used them on the railroad, beginning in the late 1880's.

Bill uses a lot of railroad slang, so for those who might be unfamiliar

with some terms, a brief glossary is presented

at the end of the article.]

To our left a field of light began to appear, a field that grew brighter

and brighter until the outline of a rugged hill was silhouetted against

it. Around the curve at the base swung the source of the illumination,

the headlight of the night local freight. The bright rays painted the

farthest house in our block with silver, continuing down the line toward

us. As the engine paused at the yard switch to head in, the headlight

beam was directly on us, and as though it had found that for which it

was searching, it held us directly in its glare. A pinpoint of light

came out of the darkness, jogging to the switch. The green signal light

changed to red and the pinpoint swung swiftly up and down. The engine

snorted, then barked furiously as it got its train into motion. The rays

of the headlight released us from durance and went about the business

of lightin' the track before it.

My friend, Bob spoke softly, "They shall teach with tongues of

fire and greatly shall knowledge increase."

"Yeah," I said, "If you're talking about those lamps,

bugs or glims out there, you're all wet. There ain't a flame or fire

in a carload of 'em-worse luck!"

My friend chuckled, "Still the old diehard. I honestly believe,

if you could have your way about it, you'd go back to diamond stacks,

link'n pins, oil headlights and the other equipment of bygone days."

"No," I

said, "Most of the changes are for the better. But take those electric

lanterns the boys are using over there," and I pointed to the little

railroad yard in front of us, "For my part, they are a pain in the

neck. Why? The field of light from those bulbs is too limited. A conductor

checking his train has the light shining right in his eyes unless he

sticks a piece of cardboard in the base as a shield. They're heavy and

you have to shut 'em off when not in use to save battery. In fact," I

continued, "there's only one thing I like about 'em and, boy, they're

grand for that. You can sure cuss the hoghead to a fare-you-well with

'em." "No," I

said, "Most of the changes are for the better. But take those electric

lanterns the boys are using over there," and I pointed to the little

railroad yard in front of us, "For my part, they are a pain in the

neck. Why? The field of light from those bulbs is too limited. A conductor

checking his train has the light shining right in his eyes unless he

sticks a piece of cardboard in the base as a shield. They're heavy and

you have to shut 'em off when not in use to save battery. In fact," I

continued, "there's only one thing I like about 'em and, boy, they're

grand for that. You can sure cuss the hoghead to a fare-you-well with

'em."

While I had been spouting, the skipper and hind man had been walking

toward the engine. The head man's light showed beside the train; he was

evidently waiting for instructions on what move to make.

The brain's lamp suddenly gave four little flickers, then was raised

and held momentarily above his head. Swiftly the head brakeman repeated

the signs and hustled back four carlengths. We heard the pop of a parted

air hose, the clatter of uncoupling; then the lamp was swung up and down

and the engine leaped ahead like cat shot with a bootjack. Again the

skipper's lamp gave two little upward flicks raised high, and a swift

pinwheel followed "Going to kick 'em with the air in 'em," I

told Bob.

The head man disappeared between the cars for an instant, then came

out an gave a hard kick sign. The engine bellowed and flung the two cars

into one the yard tracks. Another swing and the pig stopped, but the

two cars sped toward the skipper. As they passed him he ran in behind

them. A sharp, short blast of air and the wheels threw off sparks as

the air brakes clamped with a relentless grip. The local made a few more

moves, then coupled the train together and waited. Presently a string

of varnish stormed past, and the local pulled out and left us.

My friend Bob is one of those guys who never worked a day for a railroad

yet is avid for every detail he can learn about it. Me, I've put in the

greatest part of my life working for railroads and still love to spout

off about 'em any time anyone shows an interest, and sometime when they

don't. So Bob and I made a congenial pair. He'd listen attentively and

I'd rave on and on. He asked a couple of questions about lanterns and

signals. Finally I said, "All right, my eager beaver friend, you

want a lecture on railroad lanterns, by golly you're going to get an

earful. That is, if you go in the house an return with a couple of bottles

of that stuff that made a certain city famous." Bob obediently hastened

away and returned shortly with the tonsil lubricant and I began.

Just when the first railroad lanterns made their appearance I've never

learned, but the first of them undoubtedly burned whale oil. I say that

from the fact that the first American railroads were built along the

Atlantic seaboard, and whale oil was then universally used there for

illumination. Even cities used it for street lighting. I have heard that

Cincinnati, as far inland as it is, once used whale oil for street lamps.

Naturally it was expensive, and I believe it was due to that fact in

conjunction with the added fact that Cincinnati was then the largest

pork packing town in the country that led to the discovery, invention,

adoption or what have you, of the horrible compound that was used in

railroad lanterns at the time I began railroading. It was called 'lard

oil.' That stuff, judging from information given me by Mr. H. A. DeLong,

Standard Oil Co. of California, was nothing more or less than the leavings

from the lard rendering kettles. To quote Mr. DeLong, 'Lard oil was commonly

used in lanterns until a good petroleum oil was introduced. It was a

product of slaughterhouse backyard rendering plants, in which the hog

fat was cooked down to obtain lard. The lard oil used in railroad lanterns,

as nearly as we could learn, was a product left over after this rendering.

The dirty appearance you describe was probably due to kettle residue,

and because in many cases the rendering was done outdoors, dirt could

easily find its way into the material.'" Mr. DeLong adds,"The

softening point of lard oil is between 91' and 100- F."

With this latter statement I don't agree for I know from personal experience

that the stuff would stay liquid until a degree or two below freezing.

To overcome its solidifying qualities a copper wire, shaped much like

a hairpin, was run through the lantern burner. The closed end of this

hairpin was in oil and the open ends were bent towards each other in

such a fashion that the flame heated the wires, and they conveyed enough

heat into the fount to prevent the oil from congealing, except in extremely

frigid weather. I have an idea there was whale oil or something of that

sort mixed with it.

I remember being called one night to switch in the old Dyke yard. It

was colder'n a pawnbroker's heart and getting colder by the minute. Pretty

soon I saw a car whacker coming along the lead with a bucket of oily

waste. He dropped a good-sized gob of the dope at intervals just off

the tow path. I wondered what it was for, but even that early in the

game I had learned not to ask too damn many questions. However, I wasn't

long left in doubt. The switch foreman said, "Billy, let's get some

coal off these cars and start us some fires along the lead, so we can

thaw out our toes and lamps when we have to. " We all got busy piling

coal around the gobs of greasy waste and lighting 'em.

I soon found out about thawing the lamps. My lantern flame would get

smaller and weaker, threatening to expire with each move I made. Finally,

out she'd go. Then I'd run to the nearest fire, stick my tootsies almost

into it and set the lantern right on top of the coals. In a minute or

two the oil was almost boiling and that, plus the copper hairpin, would

keep the lamp going for another hour or so. Twelve hours was a shift

then, and needless to say I was darn glad when that one was over.

The lantern burner we had in those days was also a nuisance. The first

burner I ever used was like a pair of twin tubes fastened together on

one side. If you looked down on top of one it would look just like a

figure 8, each circle in the being a tube. The wick was a strand of torch

wicking, the same the hogger used in his torch, except that where he

used many strands to make it thick enough to fit the neck of his torch,

we used but one strand. We'd cut off a length of wicking and insert one

end in each of the tubes, which of course left the middle to go in the

oil fount.

There was no ratchet to turn the wick up or down; instead there was

a slot in each tube. Through this slot you'd stick a pin, toothpick,

shingle nail or any other sharp pointed object and pry the wick up or

down as needed. Most of us carried a couple of big brass pins stuck in

the lapel of our coats to use for that purpose.

Then

came the advent of the flat wick instead of the tubular. The first of

these was of felt, much the same material as in a felt hat but much coarser.

That stuff was really a bust -- no capillary action at all. They lasted,

but quick. Then came the woven wick, pretty much the same as those still

in use today. This wick, and the burner used with it, had been invented

quite awhile before, for on July 7th 1880 (eight years before I began

railroading), one Winfield S. Rogers of Columbus, Ohio was granted patent

number 233,024 covering the following claim, "Separate flanged oil

cup and wick tube and the bifurcated heater, the curved ends of which

stand askew with reference to said tube." And by golly there was

a picture of the old familiar flat wick burner with the inverted hairpin

and the slots for raising or lowering the wick. The only difference I

could see was this -- Mr. Rogers had the open points of his hairpin alongside

of the flame instead of directly in it. What advantage there was in that,

I don't know, as I never used it. Then

came the advent of the flat wick instead of the tubular. The first of

these was of felt, much the same material as in a felt hat but much coarser.

That stuff was really a bust -- no capillary action at all. They lasted,

but quick. Then came the woven wick, pretty much the same as those still

in use today. This wick, and the burner used with it, had been invented

quite awhile before, for on July 7th 1880 (eight years before I began

railroading), one Winfield S. Rogers of Columbus, Ohio was granted patent

number 233,024 covering the following claim, "Separate flanged oil

cup and wick tube and the bifurcated heater, the curved ends of which

stand askew with reference to said tube." And by golly there was

a picture of the old familiar flat wick burner with the inverted hairpin

and the slots for raising or lowering the wick. The only difference I

could see was this -- Mr. Rogers had the open points of his hairpin alongside

of the flame instead of directly in it. What advantage there was in that,

I don't know, as I never used it.

Suddenly there broke a new and glorious era -- that of "Signal

Oil" -- which was to endure for many years and which to my probably

cockeyed notion furnished the best railroad lantern fuel and light that

has yet been found. I wouldn't trade my old "copper top, Fort Scott,

signal oil lantern with No. 1 burner" [note 2]

for an even dozen of these new juice bugs, if you included a perpetual

supply of batteries. Anyhow, with the advent of signal oil, lamps began

to improve in every way. Ratchet burners came into use, though with the

first of them you had to open your lantern to turn the ratchet. If it

was windy, out went your light.

Then some guy brought one out with the little wheel on the end of the

ratchet shaft that had teeth around the edge. These teeth engaged in

holes in a circular plate fastened to the base compartment of the frame.

Rotating this movable base would rotate the ratchet shaft and thus lower

or raise the wick. It worked fine as long as everything was normal, but

if the shaft became bent or the plate was out of kilter, something that

occurred very easily, the whole shebang went haywire and the wick became

inoperative. The final and lasting improvement was simply to make the

ratchet shaft long enough to project through a slot in the base, and

you moved the wick just as on an old-style kerosene lamp in the home.

During this period of lantern trials there was a bewildering variety

of types and forms. Some oil founts were removable through the bottom

of the frame; some of them were integral with the lower part of the lantern;

some had to be taken out through the top of the lamp; some founts simply

sat in a socket in the bottom of the frame; and others were screwed into

place.

The earlier types of lanterns were poorly drafted and a swift movement

such as occurs in giving a fast, hard signal, would set up a current

of air that would extinguish the flame. One of the lanterns that was

an exception to this was that used by the old Kansas City, Fort Scott & Memphis

(now Frisco). This lamp was of an unusually light construction and had

a copper top. It was very popular with the boomers and was universally

known as the "Fort Scott copper top." Who the manufacturers

were I don't know, though I have an idea it was Dietz. In common with

many another boomer, when I left that pike one of these lamps was hanging

on my grip. I carried and used it for a long time, but finally some guy "borrowed" it

when I wasn't looking. I hope it served him as faithfully as it did me.

Brother, one could sure give a wicked sign with that baby and she'd stay

lit.

The signal oil era lasted so long that many lanterns made history during

it. Probably the most famous lantern of all time was and is the one used

by Kate Shelley on the night of July 6th, 1881 when, as a girl of fifteen,

she used it to light her way across a storm-wrecked bridge to save a

passenger train from destruction. That lantern can be seen in the Iowa

Department of History and Archives Building in Des Moines, Iowa. And

many another lantern has played its part in averting catastrophe on the

steel trails.

Back

in the years before the "Hours of Service" law came into being,

there was nothing uncommon in an engineer, fatigued by forty or fifty

hours of continuous duty, falling asleep at the throttle and failing

to act when some flagman swung his lantern across the track with a stop

signal. I wonder how many flagmen there are, who, as some engine came

storming past, ignoring his earnest, go-to-hell washout stop signs, has

stepped back from the rails and as the front of the engine cab came almost

even with him, heaved his red light smack into the window of that cab?

The startled hogger, aroused by the shower of window glass and the sudden

rush of cold air, came out of it in a hurry and usually, though not always,

in time to keep his pilot from disarranging the housekeeping in the crummy

ahead, That, thank God, is one of the conditions that no longer exists,

but honestly old-timer, have you any idea of the number of times you've

done just that? I haven't, but it is several. Back

in the years before the "Hours of Service" law came into being,

there was nothing uncommon in an engineer, fatigued by forty or fifty

hours of continuous duty, falling asleep at the throttle and failing

to act when some flagman swung his lantern across the track with a stop

signal. I wonder how many flagmen there are, who, as some engine came

storming past, ignoring his earnest, go-to-hell washout stop signs, has

stepped back from the rails and as the front of the engine cab came almost

even with him, heaved his red light smack into the window of that cab?

The startled hogger, aroused by the shower of window glass and the sudden

rush of cold air, came out of it in a hurry and usually, though not always,

in time to keep his pilot from disarranging the housekeeping in the crummy

ahead, That, thank God, is one of the conditions that no longer exists,

but honestly old-timer, have you any idea of the number of times you've

done just that? I haven't, but it is several.

A trainman's lamp was not only necessary in his work, but many times

became a weapon of defense or offense as the occasion required. A railroad

lantern with its heavy wire frame and globe was a wicked club when swung

at arm's length and with intent to damage. I saw a man come very close

to getting his head caved in by a swung lantern. He was a guard from

the California Reform School at Whittier. At that time the junction point

of the Whittier Branch and the Santa Ana Branch was a siding named Studebaker.

My partner, Charley Henry, was walking alongside of a cut of cars and

toward me. I was walking on the same side. We were each at about the

middle of two cars and would have met just about at their ends. When

Charley was just about six or eight feet from the end of the cars, out

jumped a guy and threw the powerful beam of a flashlight right into his

eyes. Charley's lamp swung over like a flash. The guy jerked his head

back, but the lantern whizzed close enough to tear his hat-brim and skin

the end of his nose. I didn't understand what it was all about, but the

fact that my partner had taken a swing at the fellow was enough for me,

so I grabbed the gent and slammed him against a car. The guard must've

begun to think he was in for some rough treatment with both of us threatening

to crown him, with our bugs.

It developed that a couple of kids had made their getaway from the Reform

School, and this guard was looking for them. We asked him if a brakeman,

carrying a lantern and working around boxcars resembled a fifteen-year-old

boy? He didn't answer that one. I'll make a sizable wager that guy never

bounced out again in front of some shack armed with a lantern.

Even in these later days the good old glim comes in handy to slug some

guy when needed. It was just a couple of years ago that skipper J. J.

Gannon of the Southern Pacific slammed a purse snatcher on the bean with

his lamp at Stockton, California. Needless to say, said purse snatcher

was still there when the cops arrived.

The trainman's or snake's lantern was not only a tool of his trade,

but in many cases became a thing of value in other respects. In the days

of lard and signal oil lamps, switch crews had regularly assigned duties

in their yards, and if work was a little light or they were smooth enough

to get it done quicker than the ringmaster figured, the crew would go

on the "spot." I'll let Haywire Mac tell it. He says, "It

was usually my luck as a newcomer to draw the coldest corner -- the one

furthest from the stove. However, all boomers knew the trick of setting

two or three lighted lanterns under the bench for warmth, and if you

could dig up an old slicker to pull over your prone carcass, a comfortable

snooze was assured. The nickel-plated electric lantern of today may be

the finest hand lamp ever devised, but it won't keep you warm in a drafty

switch shanty."

The signal oil we burned in those days was a peculiar article in some

respects. If a lamp was properly taken care of, that oil couldn't be

beat, but if a wick was submerged in it for too lengthy a period it would

lose a large part of its capillary action and would not keep the flame

supplied. Also the oil would thicken with age, change color, and you

could see thick, white specks of some matter floating in it. On the larger

railroads, the oil didn't have a chance to deteriorate. But on some smaller

roads that tried to save by buying in quantities it didn't do so well.

We always spoke of it as Galena Signal Oil." I once asked Mr. DeLong,

whom I have quoted before in this article, for the formula of signal

oil and append herewith his reply. "Signal oil could be described

as a high-test, long-burning kerosene. Its specific gravity is 35; its

flash point is 280' F. Fire point is 315' F, and pour point is 30' F." He

also adds that it is still being marketed under the name of Galena Perfection

Signal Oil. On train crews, satisfactory performance of lamps was largely

a matter of who you had for the parlor shack. The hind man usually took

care of all the lanterns belonging to the crew, and if you were lucky

enough to have one who knew how, you'd have little trouble with your

lamp going out.

My own system for caring for my lamp was to dump all the old oil from

the fount once a week, put in a new wick once a month, blow the top of

the lantern clean with compressed air frequently, and always scrape off

the crust of carbon that forms on the sides of the burner next to the

wick.

Most railroaders are very particular about their lamps, and criticism

derogatory to their appearance is not relished. I quote Mr. Edward H.

DeGroot, Jr., now an attorney in Washington, D.C. but formerly a railroader,

both in the ranks and as a brass hat. "I was very young passenger

brakeman on the CB&Q. Being 18 years of age, responsibility for that

railroad rested heavily on my shoulders. I was braking ahead for Conductor

Frank Reese and leaving Burlington on No. 4 one night, Frank had an argument

with a passenger in the smoker. It did not seem to me that enough had

been said, on the railroad's side, so when Frank went back into the train,

I walked up to the obstreperous patron and laid down the law. I was just

a skinny kid weighing possibly 140 pounds. The man looked at me in surprise,

then remarked without showing any feeling, 'Sonny, take your little greasy

tin can and run along.' No mature man of 18 relishes being called 'sonny'

and the slighting reference to the lantern on which I had spent so much

effort (wood ashes on the copper top and frame, and newspaper on the

globe) seemed gratuitous. I walked away with as much dignity as could

be mustered under the circumstances. "

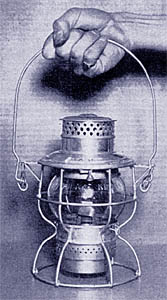

Unquestionably, the fanciest lantern carried on a railroad is and always

has been the passenger conductor's. With a heavily nickel-plated frame

and handle (the frame much smaller than the regular trainman's lamp),

and "flint glass" globe, the upper half green and the lower

half white, and the bail or handle much larger than that on a standard

lamp for ease in looping on the upper arm with the base of the lamp resting

on the bent forearm, they surely showed up grand against the brass buttons

and blue cloth of the varnish skipper's uniform. That particular type

of lantern was called the "Pullman Lantern," but I haven't

the slightest idea why.

Back in those days most railroad lanterns were made with swing handles.

By that I mean the handles were so fastened that they would drop down

just as the handle on a paiI does. That was all right for trainmen, but

yardmen didn't like them. A stiff bail was much easier to give signals

with and was far easier on their hands. So switchmen would unfasten the

bail from its regular "eye," pass the ends down through the

wires of the frame, and securely fasten them to the upright ribs. This

made the handle much shorter and made it rigid. Then they'd wrap the

wire handle with many layers of friction tape, or slip a piece of rubber

hose on it to provide a better grip. A lamp doesn't weigh such a scandalous

amount, but lug it around all night, and it'll weigh plenty come morning.

Some guy, I was told, who was or had been a snake, brought out a lamp

with a stiff, thick rattan handle. It was the answer to a switchman's

dream. That lamp was called the "Tom Moore Lantern" and was,

I believe, named after its inventor and manufacturer [note

3]. At one time there were a lot of Tom Moores in use. While down

through the years there have been many, many manufacturers of railroad

lanterns, I think there is no question that the Adlake and Dietz-made

glims greatly out-number the products of all other manufacturers.

It did not make much difference when kerosene supplanted signal oil.

True, the first kerosene lamps were not satisfactory, due mainly to the

fact they were not drafted right. After a little experimentation they

became fairly dependable, though I never had one that I could give as

swift signals without the flame going out as I could with the signal

oil lamps.

When

the Southern Pacific decided to test kerosene lanterns, ten conductors

were each given one and requested to use it thirty days and then report

on its performance and how they liked it. This was on the Los Angeles

Division and I presume other divisions made the same test. I was one

of the ten conductors. I tried to give an unbiased opinion, but that

baby could outsmoke a furnace, and you couldn't give it a good jiggle

without putting the light out. So my vote was "no." -- which

was probably one of the reasons the kerosene lamp was adopted soon after. When

the Southern Pacific decided to test kerosene lanterns, ten conductors

were each given one and requested to use it thirty days and then report

on its performance and how they liked it. This was on the Los Angeles

Division and I presume other divisions made the same test. I was one

of the ten conductors. I tried to give an unbiased opinion, but that

baby could outsmoke a furnace, and you couldn't give it a good jiggle

without putting the light out. So my vote was "no." -- which

was probably one of the reasons the kerosene lamp was adopted soon after.

We soon found that one of the littler tricks with a kerosene lamp to

prevent smoky globes was to nip a bit from each corner of the wick and

to cut a "V" in the center of it. That kept the flame from

spreading too wide and concentrated the flame into a straight column

that worked fine.

I don't know whether it was a mere idea, but in my earliest days of

railroading I was taught never to wash a lantern globe with soap and

water. I was told to just polish it dry with old train orders or cotton

waste. On my first job I was braking behind, and it was my task to clean

the lamps for the whole crew; also the desk lamp and the markers. Wanting

to make a good impression on the crew, I got a bucket of hot water from

the engine, took all the globes out of the lamps and was just about to

submerge them in the hot water when into the crummy walked my skipper,

old "Neighbor Little." When he saw what I was about to do,

he let out a whoop like an Indian.

"Don't do that, Billy," he yelled.

"What's the matter?" I demanded indignantly. "All I'm

going to do is wash these globes nice and clean."

"Not with soapy water," said Neighbor. "Don't you know

that'll take the temper outta the glass and the first time the flame

touches it, the globe'll bust all to hell'n gone and the soap will leave

a film that makes the globe smoke up twice as quick."

Well I didn't know it then and I don't know it now, but old Neighbor

was a mighty wise skipper, and I believed him absolutely.

Right

or wrong, that little piece of information has stuck in my mind ever

since, and though it was given 62 years ago, I've never washed a lantern

globe with soapy water since. The way I like to clean my lantern globe

is with a nice soft leather glove. Just stick the first two fingers down

inside the globe and revolve them round and round. Then rub the outside

briskly with the palm of the glove, and brother, that globe'll shine! Right

or wrong, that little piece of information has stuck in my mind ever

since, and though it was given 62 years ago, I've never washed a lantern

globe with soapy water since. The way I like to clean my lantern globe

is with a nice soft leather glove. Just stick the first two fingers down

inside the globe and revolve them round and round. Then rub the outside

briskly with the palm of the glove, and brother, that globe'll shine!

After a while some gent invented the electric hand lantern. I thought

it was the grandest thing I'd ever seen, and I bought one of them, for

six bucks, if I remember correctly. The battery was 65 cents extra and

supposed to burn brightly for sixteen hours continuously. Oh yeah? After

two or three hours the light began to dim like a drunk's dream. It didn't

take me long to get enough of buying a battery every few days. Besides,

I found that the field of light from that bulb was too limited. You couldn't

move around nearly as fast as with the old kerosene lamp. So my electric

bug was hung away. Yes, I still have it, out in my tool shed. Of course

the present day battery is much longer-lived than the first ones introduced.

Also the railroads now issue them without charge.

The quotation near the beginning of this article, "They shall teach

with tongues of fire" is to the point, for train crews and particularly

switching crews would be in a sad plight if they couldn't communicate

with their tongues of fire. If they had to gather together while the

foreman explained each move in advance, well I hate to think how long

it would take to make up or break up a train. As it is, they work by

a code, entirely unofficial but understood by practically every railroad

yardman in the United States and Canada, Mexico too, for that matter.

The official lantern signals as given in the Book of Rules are extremely

limited. "Apply air brakes," "Release air brakes," --

when testing brakes on a standing train. A lantern moved up and down

means go ahead; swung pendulum fashion across the line of vision means

stop; swung in a medium-size circle, back up.

A signal that is no longer necessary but is still carried in code: lantern

swung in a circle at arm's length indicates broke-in-two. Back in the

days of non-airbrake trains, when the pig jockey looked back and saw

that signal it was a case of full steam ahead and damn the torpedoes.

Yeah, he left there as rapidly as possible, earnestly seeking the lofty

brow of some hill where the hind end couldn't overtake and ram the bejazus

out of him.

There he'd wait long enough to be sure that the rear end had been stopped,

then he'd cautiously crawl back to where it stood.

And that, so far as I can remember, just about covers all the lantern

signals given in the rulebook. But the unofficial -- there's a raft of

'em. Let me quote Haywire Mac again: "This lantern code is simple

enough -- a flick of the wrist causes the lantern to blink, rather like

the dot in the Morse code. That means one. Snap it toward the pin-puller,

follow it with a kick sign and he'll let one car go. Hand the same token

to the field man and he'll line the switch for track one. Describe a

small circle with the lamp -- that spells five. A small circle followed

by one dot means six; by two dots, seven; by three, eight; and four,

nine. Ten is indicated by a big circle, not quite as large as the arm-length

'broke-in-two' of the rule book. A big circle plus one dot is eleven.

A big circle and a small circle described in the opposite direction,

means fifteen. Add a dot for sixteen, etc. Describe a big circle, reverse

direction and make another, that means twenty. If you again reverse direction

and make a small circle in addition, you have signaled twenty-five. There

seems to be but one general rule in giving these signals -- give the

largest number first and follow with the smaller ones. For example, first,

a big circle for ten, next a small circle (reversed direction) for five,

and lastly a dot. Ten plus five plus one equals 16."

There are a few other unofficial lamp signals, mostly used by trainmen.

To pull or put cars on a track that has no number, a lantern moved with

a sweeping movement between the rails of that track is indication which

track to make a move on. A figure 8 swung with a lamp close to and parallel

with the ground means that a car chain is needed. When shoving to a coupling

with quite a few cars, the brakeman will in many cases, give the hogger

the distance to the coupling by throwing him car-length signs. Three

sweeps overhead (reverse of stop) means "three car lengths to coupling," etc.

Knowing the condition of his driver brakes and having the feel of the

weight of his cut, the hogger can do a much better job of driving to

a joint. The well-known highball is, of course, merely a go-ahead signal

swung at full arm's length."

Now friend Robert, you asked for it, and by golly, you got it. And if

you'll now proceed to the refrigerator and return with a couple of bottles,

we'll drink to the health of all lantern carriers, in the yards or on

the trains.

Notes

1. Railroad magazine was eventually taken

over by Carstens Publications before merging into "Railfan and Railroad" magazine

which continues to this day. Hal Carstens of Carstens Publications informed

us that the copyright to this article reverted to Bill Knapke, who passed

on some time ago. Current copyright ownership is unknown. We are reprinting

this article anyway -- somewhat abridged for the web -- because we feel

that Bill would have wanted current collectors to read his very interesting

memoirs.

2. The phrase "Fort Scott copper top" is

puzzling, since lanterns with actual copper tops are almost unheard of.

This may refer to a brass top lantern.

3. This is the well-known T.L Moore switchman lantern,

shown on the switchman lantern page.

Glossary of Railroad Slang

- boomer: brakeman, often one who worked for a

short time, then moved on.

- brain: conductor

- brass hat: railroad official

- bug: lantern

- car whacker: car inspector

- crummy: caboose

- glim: lantern

- head man: head brakeman

- hind man: rear brakeman

- hoghead: engineer

- joint: a coupling of railroad cars

- parlor shack: caboose

- pig: locomotive

- pig jockey: locomotive engineer

- pin puller: brakeman who is uncoupling cars

- snake: brakeman

- skipper: conductor

- varnish: passenger train

|